|

Rev David Merwin

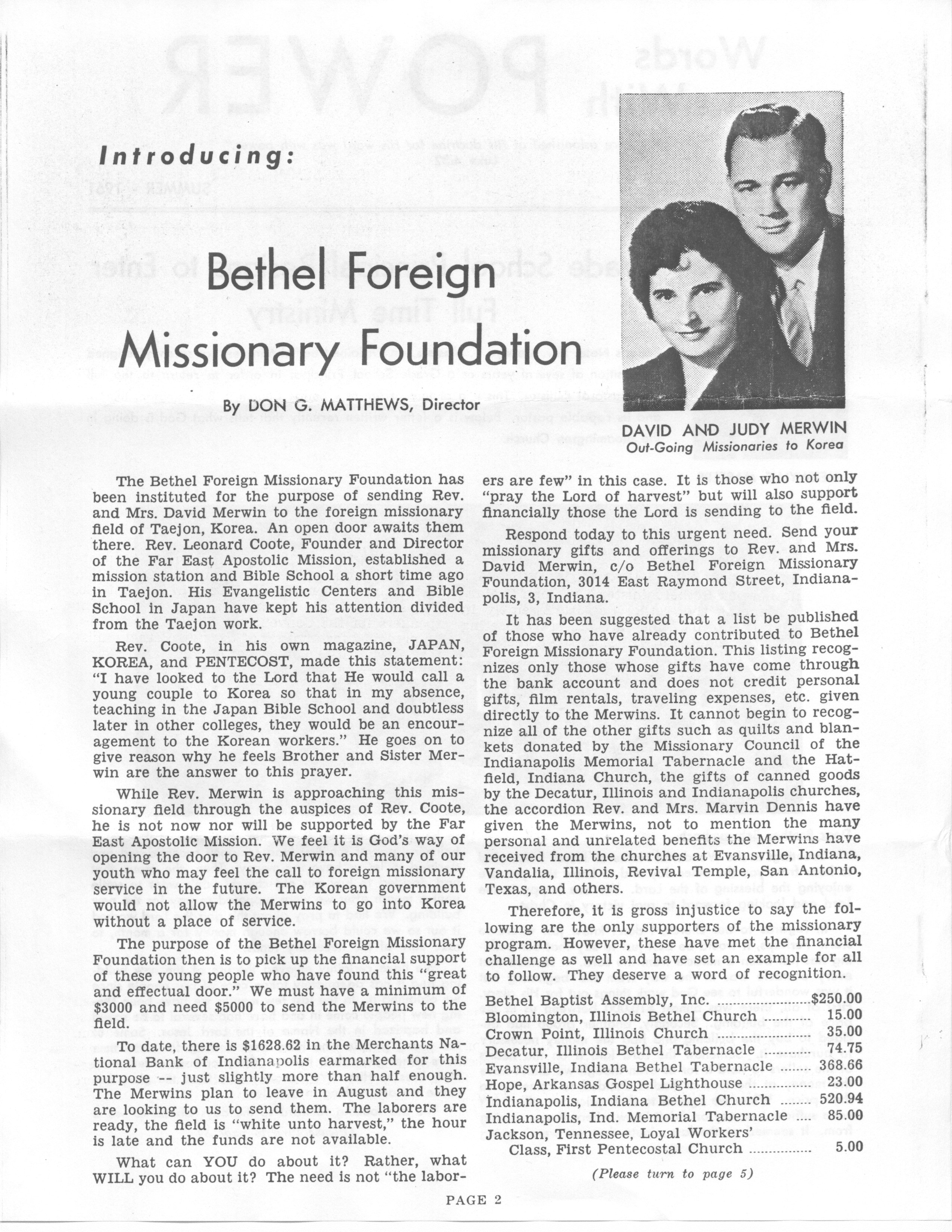

Reverend David Merwin, formerly of Clear Lake, Oregon, was 63 when he passed away Aug. 29, 1995, at St. Vincint's Hospital, Portland, Ore. Rev. Merwin served in the United States Army in Korea, and later went back to Korea to minister as a Missionary for many years. Upon returning to the United States he pastored churches in Evansville, Ind., and Portland, Ore.He was survived by his wife, Judy, of Alaho, Ore.; two daughters, Stephanie and her husband, Darrald Fast, and Sarah and her husband, Michael Miller; four grandchildren; four brothers, Arthur Merwin and his wife, Mabel, Clear Lake, Jim Merwin, Clear Lake, Ralph Merwin and his wife, Helen, Franklin, Tenn., Paul Merwin of Jackson, Tenn., Carol May and her husband, E.C. Wilson, Jackson, Tenn., Althea McClendon, Henderson, Tenn., Sara and her husband, Ed Lyon, Memphis, Tenn., and Pauline and her husband, Sam Milam, Paducah, Ky. |

|

The BMA sends the Merwins into the Field. |

|

Outcast For I will restore health unto thee, and I will heal thee of thy wounds, saith the LORD; because they called thee an Outcast, saying, This is Zion, whom no man seeketh after. - Jeremiah 30:17 I will go before thee, and make the crooked places straight: I will break in pieces the gates of brass, and cut in sunder the bars of iron: - Isaiah 45:2 < >< "THE OUTCAST" (The story of Stephanie Fast, Written by Stacy Wiebe) Stripped of dignity and hope, beaten and malnourished. The abandoned six-year-old lay on a mound of garbage wanting to die. Then out of nowhere, a ray of sunshine pierced the black hole that enveloped her. The city of Daejon was just waking up, still trying to forget the nightmare of the Korean War, when eight year-old Stephanie slipped through the orphanage gate into the day's first light. Her skinny arms formed a circle around a bundle of smelly rags. As the oldest in the orphanage, it was her job to wash all the diapers. She walked two miles to the river, where she beat the diapers clean with a wide stick and sloshed them around in the icy water. By mid-afternoon, she was heading back to the orphanage to hang them up to dry. It was hard work, but Stephanie didn't mind. Especially not today. Yesterday, the Swedish nurse, Iris Erickson told her: "Please help get all of the children ready. The foreigners are coming." On the way back to the orphanage, a string of kids followed Stephanie, shouting, as they always did, "Toogee! Toogee!" She didn't look at them, and walked on, her thoughts focused on all that had to be done at the orphanage. Stephanie was used to people hassling her on the streets, and inside she believed that nasty word - Toogee - was really her name, her true identity. In English it means foreign devil. "I thought I was the lowest you could get," says Stephanie. "That I was worse than a dog or pig and that my face was twisted and grotesque." But it was her curly hair and big, bright eyes that made people hate her. To the Koreans, she was "a child of foreigners"- a "devil" fathered by an American G.I. She was a reminder of everything they wanted to forget. HOPE FOR A FUTURE The orphanage chimes echoed throughout the compound. "I hope we didn't forget anything," Stephanie thought. She had spent hours scrubbing the babies, trying to make them as pretty as she could, even putting little ribbons in the girls' hair. "One of these babies is going to America," she said to herself, straining to hear the voices outside the gate. "And they're going to have a future." The door squeaked open, and the worker motioned for the American couple to come in. Already they had been to six orphanages, looking for a little boy to call their own. They had already chosen a name for him, too: Stephen. Fear and amazement gripped Stephanie's entire 30-pound body as she stared at the couple towering in the doorway. She had seen foreigners before - American soldiers and Miss Erickson, the blue-eyed nurse who took her off the streets into the orphanage almost two years ago. But these people now passing through the gate weren't like any Americans she knew before. "They were the tallest, roundest and strangest looking people I had ever seen," recalls Stephanie. Stephanie watched, fascinated as the huge man picked up a tiny baby and tucked it under his arm. Then she saw something else she had never seen in her life: tears trickling down a man's face. As she was trying to figure out why, Stephanie found herself edging closer to where he was. She stopped, frozen, when he looked at her with wet eyes. He crouched in front of her and made noises with his lips she didn't understand as he spoke quietly to her in English. Her hair was more white than brown, teeming with lice. She was covered with boils and jagged scars. She had worms that sometimes crawled out through her ears or her mouth. Her left eye rolled around lazily in its socket. Now suddenly the man's massive hand was coming toward her face. It landed softly on her cheek and covered her like a smooth blanket. He stroked her, ever so gently. "My heart did a somersault." Stephanie remembers. "Inside I wanted to say, don't take that hand away, please love me." Instead, she yanked off the hand and spat on him. A DARK PAST Before she came to live at the orphanage, when she was living on the streets, Stephanie determined that no matter what anyone did to her body, they would never hurt her on the inside. When some farmers tied her naked to a tree and let their children jab different parts of her body with sticks to see how she would respond to the pain, Stephanie learned not to cry. "You don't let people know that you hurt, because the more you let them know that you hurt, the more pleasure it seems to give them," she explains. "By the time I was six I was dead emotionally." Ever since her mother abandoned her - Stephanie thinks she remembers her sending her away alone on a train when she was about four - she had been running from village to village. She slept in caves, or under bridges and roasted locusts on rice straw or sucked the marrow from the bones the butchers threw out. Stephanie wanted to survive, and she kept hoping that her mommy or her daddy would be waiting somewhere for her. But many of the Korean villagers wanted to get rid of her. She was an ugly reminder of an ugly war. A group of men once tied her to a waterwheel, hoping to drown her. Her mouth filled with mud and blood as she went round and round, thrashing and listening to the people laugh. Then, she heard a man's voice, deep and strong, telling them to stop. The man untied her and said to her, "Run, little girl, run. These people, they will hurt you." To this day she wonders if maybe he was an angel. In the city, Stephanie became skilled at snatching food from the marketplace. But one time, because she was carrying a little girl she had found on the street, she was caught. "I remember being grabbed by a man and pulled back by my hair. And he said, 'It's that dirty Toogee again'. He recognized me somehow." Stephanie and the little girl were thrown over a wall into a bombed-out building that was infested with rats. "I held the little girl and rocked and screamed," Stephanie said. "I fainted, probably out of fear. I don't know how long I was out, but when I woke up, I saw with my six-year-old eyes how the rats had eaten away at that little girl." Miraculously, someone rescued Stephanie. Soon after, Stephanie contracted cholera. "At seven years of age, I wanted to die," Stephanie recalls. "I knew what my future was, I hated myself and everything around me, especially the people. I didn't want to be abused anymore." That's when, in 1960, Iris Erickson found her laying on a garbage heap and brought her to live in the orphanage. Two years later, Americans David and Judy Merwin came to adopt a baby. HOME "You're not going to believe this," David Merwin told his wife Judy on the way home from their visit to the orphanage, "but I have this feeling that we're supposed to adopt that little girl - the one who spit on me." Judy Merwin laughed. She had that same stirring in her heart - and she felt it was from God. So the next day the Merwins returned to the orphanage and the little girl became their Stephanie. Suddenly Stephanie had her own room and her own bed. And suddenly she had an identity. She was Stephanie Ann Merwin. And she was an American. Stephanie soon discovered that Americans like people who smile a lot. In a crowd of friends, she was always the bubbly one. As she grew older, she bleached her hair and talked her mom into buying her blue contacts, all so she would look more American. "But inside I didn't feel American or Korean, I was a dirty, ugly Toogee," Stephanie admits. Stephanie's parents only knew the little about her past that the orphanage told them - just that she was found on the streets and that she was bi-racial. But the Merwin's were troubled when they returned to Korea as missionaries after spending a year in the United States. Stephanie, at 12, always sat in the back of the church with her arms folded, and refused to speak to Korean people. She wanted to forget her past at all cost. But her outer facade of happiness was wearing very thin during her late teens. She began pulling away from everyone in her life, and whenever she talked about herself, it was always negative. "I was full of bitterness and confusion and pain inside," says Stephanie. But she didn't want anybody to touch that - not her parents, and definitely not God. One day her dad came up to her room, and sat at the end of the bed. He said, "I want to talk to you once more about Jesus." Stephanie remembered thinking, "Hey, I'm a walking encyclopedia when it comes to Jesus. I've been going to church most of my life, and I've been baptized. I don't need that anymore." But Stephanie listened to her dad as he spoke gently to her. He talked about how when Jesus left heaven for earth, that he was conceived outside of marriage by a virgin. "He also asked if I'd thought about where Jesus was born," says Stephanie. "To me, the manger was just like the Christmas play every year. I didn't realize that it was a dark, dirty cave that never got cleaned out and that the only thing he had for a bed was a feeding trough." Stephanie's dad went on to explain how King Herod wanted to kill Jesus when he was a child because of what he represented, and how later on in life even his closest friends rejected him. Stephanie began to cry as she realized how Jesus had been abused, and eventually even killed, so that He could identify with her. It was the first time she cried since she'd been thrown into the building with the rats. She prayed, opening up her life to God, asking Him to take her past, to forgive her sins and to make her whole. That day was the beginning of a healing that's still happening in Stephanie's life. When she married her husband Darryl right out of high school, he knew she was adopted, but he didn't have an inkling of what her past really was. When Stephanie began to have nightmares, Darryl knew that they were more than just normal dreams. As Stephanie opened up to him, they began to work through her past, and to pray together for God's help and healing. Part of that healing has come since Stephanie began sharing her story publicly. She has a special concern for women, who often struggle with their sense of identity, and have been in abusive relationships. Stephanie is a regular speaker for women's groups and has traveled across the world to tell her story, even to Korea. As she talks about her life, Stephanie still marvels that she survived those childhood dangers and realizes how fortunate she is to be alive and doing what she's doing today. "You know, it was amazing, but every time I was in trouble, there was always someone who rescued me," Stephanie recalls. "And each time the person would tell me, 'Little girl, you must live.' I don't know if they were angels or just people God used, but I do know that God spared my life. He never gave up on me. And I've learned He never will." *Stephanie Fast and her husband Darryl have two sons, Stephen and Davin. They live in Oregon in the United States. < >< If the Son therefore shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed. - John 8:36 http://www.gagirl.com/tidings/051500.html For the first few years of her life Stephanie didn’t have a name, but people called her “Toogee” – that’s Korean for “foreign devil.” It was her curly hair and big, bright eyes that gave her away, and made people hate her for the bastard child of an American G.I. that she was. She was a reminder of everything they wanted to forget. When she was just four years old her mother abandoned her. Stephanie thinks she remembers her mother sending her away alone on a train. And since then she’d been surviving by sleeping in caves or under bridges, and eating locusts or scraps of food people tossed out, or things she was able to steal from the marketplace. She moved from village to village hoping that her mommy and daddy would be waiting for her somewhere. But many of the Korean villagers wanted to get rid of her. At one point a group of men tied her to a waterwheel hoping to drown her. Round and round she went, in and out of the water, her mouth and nose filling with water and mud, when suddenly the wheel stopped, and a kind man untied her and said to her, “Run, little girl, run. These people will hurt you.” By the age of six, she says, she was dead emotionally. At seven years of age, she recalls, “I wanted to die. I knew what my future was, I hated myself and everything around me, especially the people, [and] I didn’t want to be abused anymore.” And so, stripped of dignity and hope, beaten and malnourished, and now suffering from cholera, she lay down on a garbage heap and waited to die. But that’s when her whole world entirely changed. She was found lying there on the garbage heap by Swedish nurse by the name of Iris Erickson, who took her off the streets and brought her to live in the orphanage that she operated in the city. Two years went by, during which her hope faded of ever being adopted, until the day came when an American missionary couple, David and Judy Merwin, arrived at the orphanage. They’d already been to six other orphanages, looking for a little boy to call their own. They’d already chosen a name for him, too: Stephen. “They were the tallest, roundest and strangest looking people I had ever seen,” Stephanie recalls. But they were instantly drawn to her. And so the very next day the couple adopted her into their family. And suddenly, the little girl who for almost nine years of her life had, even in her own mind, no other identity than “Toogee” – an outcast, foreign devil – became Stephanie Ann Merwin. And she was an American, with all the rights and privileges that we so freely enjoy. She was loved by her new parents, and she learned about the love of God in the Bible, and was baptized. And yet she didn’t know how to accept the love of either her parents or of God, because still, inside, she didn’t feel like anything but a dirty, ugly toogee. Until her new mother sat down with her one day and explained that when Jesus came down from heaven to be born of a virgin, he too was ridiculed and mocked as an illegitimate child. Some even said he was the base-born son of a Roman soldier. Her mother also asked her if she’d ever thought about where Jesus was born. “To me,” she says, “the manger was just like the Christmas play every year.” She never realized that it was a dark, dirty cave that never got cleaned out and that the only thing he had for a bed was a feeding trough.” Stephanie’s mother went on to explain how King Herod had tried to kill Jesus when he was a child because he felt him to be a threat, and how later on in life even his closest friends rejected him. That’s when Stephanie began to realize that Jesus, the Son of God, went through all of that abuse, and was eventually killed, to become one with us, so that we could become the children of God, and be loved by Him. And so from that day on, Stephanie began to grow in her joy, not only in her adoption as the free daughter of the Merwins, but in her adoption as the free child of God through her union with Jesus Christ. Do you have joy in your adoption? St. Paul’s parable of the two mothers, the two wives of Abraham in our epistle lesson, illustrates our good fortune in being made children of promise by the free woman. Sarah represents the Jerusalem above, the Church, who has birthed us into union with the one true Son, that birth which is, says Paul, “according to the Spirit” – the Spirit of adoption, by whom we cry out to God, “Abba, Father.” And St. Paul contrasts this blessing with the bondage and curse that we were adopted out of – the bondage and curse of the Law. Hagar, the slave women, represents, the Jerusalem which then was, the Old Covenant Church under the Law, whose children were in bondage with her. All of us when we were born merely “according to the flesh” had this woman for our mother. And she was brutal. All she could ever do was call us down for coming up short of her expectations. All she could ever do is batter and bruise our consciences because of our sins. All she could ever see in us was an evil toogee – a foreign devil. But thanks be to God, “when the fullness of time had come God sent forth His Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, that we might receive the adoption as sons” (Gal. 4:5). Thanks be to Christ that, though we were foreigners to God’s people and strangers from the covenants of promise, now in Jesus Christ we are no longer strangers and foreigners, but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God (Eph. 2:12, 19). And that means we’re free. Free of the bondage and curse of the Law. Free of fear of God’s rejection of us. Free to love God with joy and gratitude in our adoption. “For you did not receive the spirit of bondage again to fear, but you received the Spirit of adoption by whom we cry out, “Abba, Father.” (Rom. 8:5). http://www.ststephensmontrose.com/files/Fourth_Sunday_in_Lent_2009.htm |

| Contact Rev Dave Matthews at davem3333@aol.com if you have something you would like to add to this section about Brother Merwin. |

DaveM3333@aol.com

page created by daveweb1.com

|