|

The History of the Bethel Ministerial Association

As an amateur historian and the unofficial historian of the Bethel Ministerial Association, I am attempting to write a

history of the BMA so what we know may be preserved for the future. I have put it on this website so that those who

probably know the history far better than I do may read it, critique it, offer corrections and inputs so we can get a history

that is as close to accurate as we can possibly make it. If you are one of these individuals, please feel free to send me

an email at davem3333@aol.com with any comments you may wish to submit. I hope we

produce a somewhat comprehensive document before I also am too old to remember it. Enjoy!

|

|

“Seymour and his small group of new followers soon relocated to the home of Richard and Ruth Asberry at 214 North Bonnie Brae Street. White families from local holiness churches began to attend as well. The group would get together regularly and pray to receive the baptism of the Holy Spirit. On April 9, 1906, after five weeks of Seymour's preaching and prayer, and three days into an intended 10-day fast, Edward S. Lee spoke in tongues for the first time. At the next meeting, Seymour shared Lee's testimony and preached a sermon on Acts 2:4 and soon six others began to speak in tongues as well, including Jennie Moore, who would later become Seymour's wife. A few days later, on April 12, Seymour spoke in tongues for the first time after praying all night long. “News of the events at North Bonnie Brae St. quickly circulated among the African American, Latino and White residents of the city, and for several nights, various speakers would preach to the crowds of curious and interested onlookers from the front porch of the Asberry home. Members of the audience included people from a broad spectrum of income levels and religious backgrounds. Hutchins eventually spoke in tongues as her whole congregation began to attend the meetings. Soon the crowds became very large and were full of people speaking in tongues, shouting, singing and moaning. Finally, the front porch collapsed, forcing the group to begin looking for a new meeting place. A resident of the neighborhood described the happenings at 214 North Bonnie Brae with the following words: “‘They shouted three days and three nights. It was Easter season. The people came from everywhere. By the next morning there was no way of getting near the house. As people came in they would fall under God's power; and the whole city was stirred. They shouted until the foundation of the house gave way, but no one was hurt.’ “The group from Bonnie Brae Street eventually discovered an available building at 312 Azusa Street in downtown Los Angeles, which had originally been constructed as an African Methodist Episcopal Church in what was then a black ghetto part of town. The rent was $8.00 per month. A newspaper referred to the downtown Los Angeles building as a "tumble down shack". Since the church had moved out, the building had served as a wholesale house, a warehouse, a lumberyard, stockyards, a tombstone shop, and had most recently been used as a stable with rooms for rent upstairs. It was a small, rectangular, flat-roofed building, approximately 60 feet (18 m) long and 40 feet (12 m) wide, totaling 2,400 square feet (220 m2), sided with weathered whitewashed clapboards. The only sign that it had once been a house of God was a single Gothic-style window over the main entrance.  The Apostolic Faith Mission on Azusa Street, now considered to be the birthplace of Pentecostalism. “Discarded lumber and plaster littered the large, barn-like room on the ground floor. Nonetheless, it was secured and cleaned in preparation for services. They held their first meeting on April 14, 1906. Church services were held on the first floor where the benches were placed in a rectangular pattern. Some of the benches were simply planks put on top of empty nail kegs. There was no elevated platform, as the ceiling was only eight feet high. Initially there was no pulpit. Frank Bartleman, an early participant in the revival, recalled that ‘Brother Seymour generally sat behind two empty shoe boxes, one on top of the other. He usually kept his head inside the top one during the meeting, in prayer. There was no pride there.... In that old building, with its low rafters and bare floors...’ “By mid-May 1906, anywhere from 300 to 1,500 people would attempt to fit into the building. Since horses had very recently been the residents of the building, flies constantly bothered the attendees. People from a diversity of backgrounds came together to worship: men, women, children, black, white, Hispanic, Asian, rich, poor, illiterate, and educated. People of all ages flocked to Los Angeles with both skepticism and a desire to participate. The intermingling of races and the group's encouragement of women in leadership was remarkable, as 1906 was the height of the "Jim Crow" era of racial segregation,[10] and fourteen years prior to women receiving suffrage in the United States. “Worship at 312 Azusa Street was frequent and spontaneous with services going almost around the clock. Among those attracted to the revival were not only members of the Holiness Movement, but also Baptists, Mennonites, Quakers, and Presbyterians. An observer at one of the services wrote these words: ‘No instruments of music are used. None are needed. No choir- the angels have been heard by some in the spirit. No collections are taken. No bills have been posted to advertise the meetings. No church organization is back of it. All who are in touch with God realize as soon as they enter the meetings that the Holy Ghost is the leader.’ “The Los Angeles Times was not so kind in its description: ‘Meetings are held in a tumble-down shack on Azusa Street, and the devotees of the weird doctrine practice the most fanatical rites, preach the wildest theories and work themselves into a state of mad excitement in their peculiar zeal. Colored people and a sprinkling of whites compose the congregation, and night is made hideous in the neighborhood by the howlings of the worshippers, who spend hours swaying forth and back in a nerve racking attitude of prayer and supplication. They claim to have the "gift of tongues" and be able to understand the babel “The first edition of the Apostolic Faith publication claimed a common reaction to the revival from visitors: ‘Proud, well-dressed preachers came to 'investigate'. Soon their high looks were replaced with wonder, then conviction comes, and very often you will find them in a short time wallowing on the dirty floor, asking God to forgive them and make them as little children. “Among first-hand accounts were reports of the blind having their sight restored, diseases cured instantly, and immigrants speaking in German, Yiddish, and Spanish all being spoken to in their native language by uneducated black members, who translated the languages into English by ‘supernatural ability.’ “Singing was sporadic and in a cappella or occasionally in tongues. There were periods of extended silence. Attenders were occasionally slain in the Spirit. Visitors gave their testimony, and members read aloud testimonies that were sent to the mission by mail. There was prayer for the gift of tongues. There was prayer in tongues for the sick, for missionaries, and whatever requests were given by attenders or mailed in. There was spontaneous preaching and altar calls for salvation, sanctification and baptism of the Holy Spirit. Lawrence Catley, whose family attended the revival, said that in most services preaching consisted of Seymour opening a Bible and worshippers coming forward to preach or testify as they were led by the Holy Spirit. Many people would continually shout throughout the meetings. The members of the mission never took an offering, but there was a receptacle near the door for anyone that wanted to support the revival. The core membership of the Azusa Street Mission was never much more than 50–60 individuals with hundreds and thousands of people visiting or staying temporarily over the years. |

Leaders of the Apostolic Faith Mission on Azusa Street “By the end of 1906, most leaders from Azusa Street had spun off to form other congregations, such as the 51st Street Apostolic Faith Mission, the Spanish AFM, and the Italian Pentecostal Mission. These missions were largely composed of immigrant or ethnic groups. The Southeast United States was a particularly prolific area of growth for the movement, since Seymour's approach gave a useful explanation for a charismatic spiritual climate that had already been taking root in those areas. Other new missions were based on preachers who had charisma and energy. Nearly all of these new churches were founded among immigrants and the poor. “Many existing Wesleyan-holiness denominations adopted the Pentecostal message, such as the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee), the Church of God in Christ, and the Pentecostal Holiness Church. The formation of new denominations also occurred, motivated by doctrinal differences between Wesleyan Pentecostals and their Finished Work counterparts, such as the Assemblies of God formed in 1914 and the Pentecostal Church of God formed in 1919. An early doctrinal controversy led to a split between Trinitarian and Oneness Pentecostals, the latter founded the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World in 1916.” Brother Varnell was 11 when the revival began. We must assume that he associated with friends from what would become the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, as recorded by its associations’ history, and then developed that relationship in his young life leading up to World War I. He was 19 when the war began and 23 at its end, November 11, 1918. Interestingly, his registration card gives some revealing information about Brother Varnell. He lists his address as 819 E. Second St, Santa Ana, California. He lists his present occupation as “mission work” but states that he was not employed at that time. He also claims exemption to his draft status due to “religious views.” Also interesting is that at age 22, he is still unmarried. The back of his registration card describes Brother Varnell as being tall, medium build with grey eyes and dark brown hair.  The historical record of the PAW verifies Brother Varnell’s early life and association with their newly established organization. “Varnell was drafted into military service in 1917-18 for WW1, but the PAW had ministerial exemption from combat, and apparently he was not required to serve. By 1919, he was living in Sacramento (CA), according to the 1919-20 PAW Minute Book. “His passion for ministry was nurtured by Booth-Clibborn, whom he traveled with doing tent revivals for the next few years. When Booth-Clibborn felt Varnell was sufficiently ready, he gave him all of his accroutraments (tent, piano, platform, chairs, and pulpit). Upon examining the pieces, Varnell discovered that Booth-Clibborn had left a surprise gift in the pulpit compartment – a copy of many of his sermon notes. |

Early photo of Rev A.F. and Rachael Varnell “Varnell and his wife, Rachel (who played piano) conducted tent revivals until money ran out, then would go back to California and do odd jobs until they could afford another revival. Their strategy was to plant churches, raise up leaders, and turn the churches over to those leaders. Following numerous invitations to conduct tent revivals, they were invited to Illinois. There they began to settle and plant churches in the Midwest. “Perhaps due to his evangelistic work, a 27 year old Varnell was appointed to the PAW Missionary Board, chaired by Elder William Mulford in 1922. The following year, he served on the PAW Credentials & Grievances Committee. “1924 was a year that PAW Historian Morris Golder called “the year of disaster.” It was also the first convention that Elder Garfield T. Haywood served as Chairman. The Texas delegation had come to the 1923 convention with a proposal to split the organization into two separate operating units—one ‘colored’ and one white. “At the 1924 convention, they moved for action on this, with other additions. They included: * a name change for the organization, * a division of the signing of credentials by race, * and separate printed material and literature. “It was also learned that the southern brothers had been holding a separate regional conference since 1922. “When their proposal was rejected, the majority of white PAW ministers (led by Howard A. Goss and William E. Kidson) met in a separate room, in the same hotel. There they formed a new all-white organization (the Pentecostal Ministerial Alliance), and left the PAW. “Meanwhile, Albert F. Varnell, the son of the segregated south, did ‘not’ join this organization. . . opting to remain a member of the interracial PAW. The strength of that decision is even more impressive when you consider that his mentor and friend, Elder William Booth-Clibborn, did join. Booth-Clibborn, a longtime member of the PAW, was the grandson of William Booth (who founded the Salvation Army). “The next year, when the organization moved from a presbytery to an episcopal style leadership, A. F. Varnell was selected one of the first five Bishops of the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World. “Having faithfully served through the contentious ‘23 and ’24 conventions, Elder Albert F. Varnell of Vandalia (IL) became Bishop Albert F. Varnell at the 1925 PAW Convention. He and Bishop Glen Beecher Rowe of Mishawaka (IN) joined African-American Bishops Alexander R. Schooler, Joseph M. Turpin and Garfield T. Haywood as the organization’s first five Bishops. |

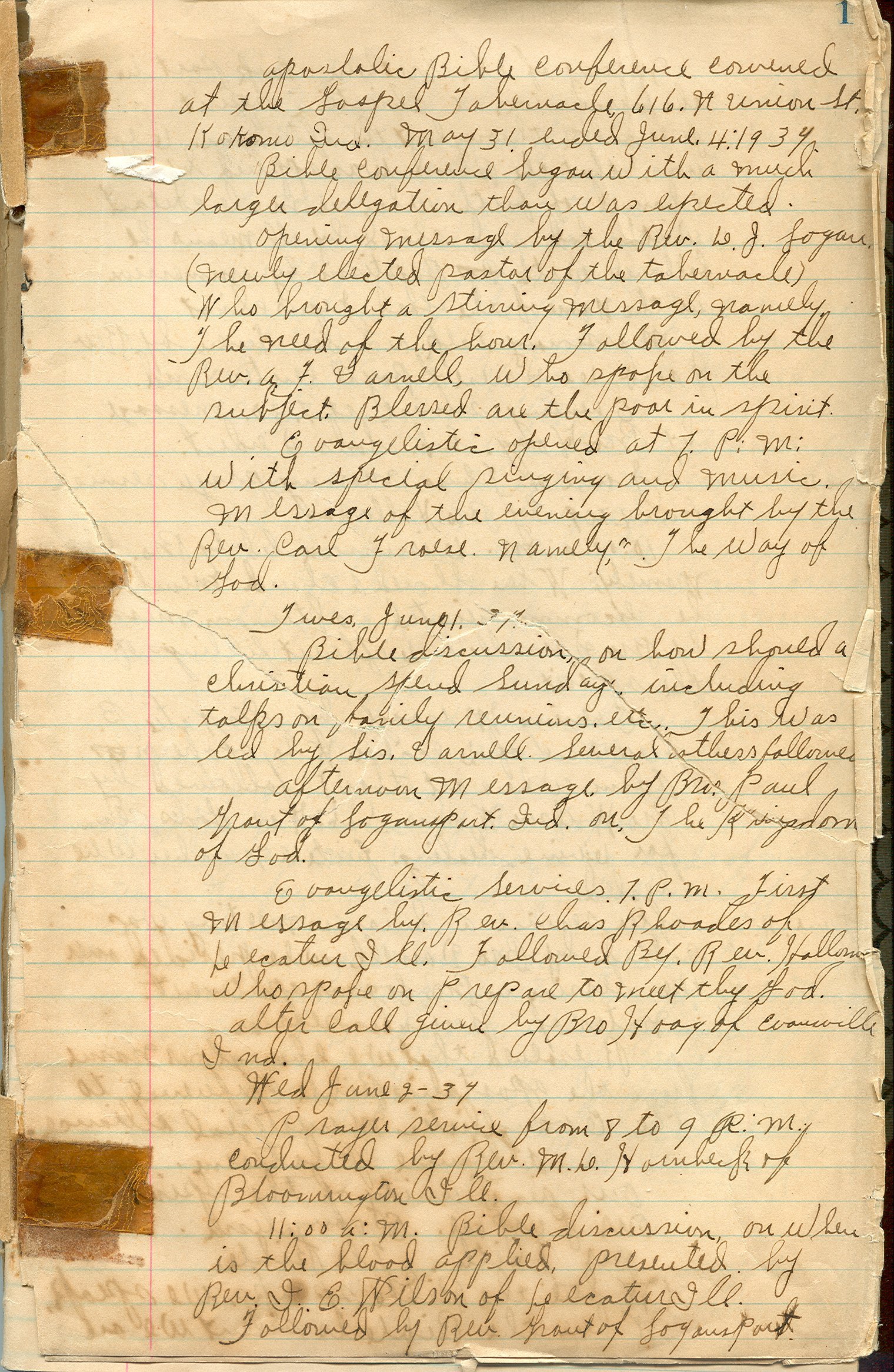

1925 Record of Original Bishops of the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World “Varnell served as Bishop until 1929, when he exited the PAW. He remained a staunch defender of baptism in Jesus name, taught that “speaking in tongues is the highest form of worship,” and taught that all believers should earnestly seek the pentecostal experience. However, he differed with the organization’s orthodoxy that tongues is the initial evidence of the indwelling Holy Ghost. Even so, Varnell kept fellowship with several PAW colleagues after his separation.” “Varnell’s wife, Rachel wrote two articles in the July 1932 issue of The Apostolic Herald, official publication of The Pentecostal Church Inc. This indicates that Varnell apparently associated with the PCI (founded by Howard A. Goss) after leaving the PAW. However, when the PCI required all ministers to accept initial evidence in 1933, “and preach it or they would not be permitted to remain in good standing,” Varnell also left the PCI. “He had recently accepted the invitation of a group of 15 Christians in Evansville (IN) who had no pastor, but had begun meeting together. So Varnell returned to Evansville and resumed pastoring the Emmanuel Gospel Lighthouse. “The following June, he convened a group of 20 pastoral colleagues and founded the Apostolic Bible Conference in Kokomo (IN), near Indianapolis. Before that meeting concluded, the group became known as the Evangelistic Ministerial Alliance. “In 1935, Varnell assumed the pastorate of the Apostolic Church of Belleville (IL). He was there until 1937. Apparently, juggling pastorates in both Illinois and Indiana during that time, Varnell resigned the Belleville congregation (which is currently affiliated with the United Pentecostal Church). “Rev. A.F. Varnell returned to Evansville (IN) and pastored at Emmanuel until 1947. He then released the leadership to Rev. R.R. Schwambach, one of his protégés. That church, now named Bethel, currently touts more than 2,000 members. “Varnell returned to lead the EMA, and in 1951 changed its named to Bethel. He established the Bethel Publishing House and distributed more than 20 self-authored doctrinal tracts on various subjects. The EMA is now known as the Bethel Ministerial Association. “Following the death of his wife Rachel around 1959, Varnell returned again to California— this time to Santa Ana. There he married Ruth Seely, whom his first wife recommended for him. He lived there and mentored young ministers, including R.R. Schwambach’s son Steve (when he entered the ministry) in 1967. Rev. Steve Schwambach pastored Bethel for 33 years, following his father. “Albert Franklin Varnell passed in April 1979 and was buried in his native Arkansas, at Booneville’s Oak Hill Cemetery. “His legacy in the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, is a significant one. Whether as an evangelist, Foreign Missions Board member, Credentials & Grievance Committee member, he is a key historical figures that maintained defense of Jesus name baptism and advocated speaking in tongues throughout his life. “One of the PAW’s first roster of Bishops, A.F. Varnell should be remembered as one that stood tall in the face of enormous tension, at a pivotal time in our history.” He was a “little known, yet significant contributor to the PAW Legacy and was one of the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World’s first five Bishops, during a time that took great courage for him to support the organization. “Albert Franklin Varnell is an unsung figure in the history of the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World. Yet, at a pivotal moment in this organization’s early development, A.F. Varnell stood admirably against the prevailing winds of society, in favor of a strong and united PAW. “We find that A.F. Varnell was, in fact, a very active voice for name of Jesus baptism and oneness theology throughout his life . . . even after departing the PAW. And importantly to our organization, his service to the PAW itself was significant. Rev. Don Matthews, who was mentored by “Doc” Varnell, recalls accompanying him to Christ Temple (Indianapolis) to preach. On another occasion, Matthews later recalls sitting in Pastor Morris Golder’s office, prior to his preaching at Christ Temple, and seeing a photo of Varnell on the pastor’s desk.” Brother Varnell certainly impacted the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World in an extremely positive way. But, as one chapter with the PAW ended, he could be easily found championing the cause of Christ in what was to become the Bethel Ministerial Association. |

|

Click here to return to home |

DaveM3333@aol.com

page created by daveweb1.com

|